One of the most important things we as teachers need to know about is our students' needs. We need to know thoroughly about all our students and of course, students with special needs come on top of the list.

Here is another finding for me about students special needs in which I summarize and combine in one post.

I hope you would find it beneficial as I did.

Source: www.theschoolrun.com

10 Things You Need To Know About Autistic Spectrum Disorders In Children

Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are often difficult to understand and diagnose. We take a look some of the key things to know about them and how they could affect children.

1. Autism affects the ability and desire to connect with other people.

2. Some children have difficulties alongside their autism, which may affect their education and their overall emotional and social development.

3. Most children with autism look as ‘normal' as any other child through their behavior and possibly their speech may make them seem different.

4. Some children with autism are not diagnosed for a while, as the symptoms of autism are not always clear-cut.

5. Autistic children can have serious communication difficulties and often this only becomes clear as they emerge from babyhood.

6. Although there is no actual cure for autism, some people do develop ways of living independently and overcome some aspects of the condition.

7. Interventions for children with autism range from communication-based approaches such as PECS (Pictorial Exchange Communication System) to more traditional techniques.

8. It's estimated that there are more than half a million people in the UK with autistic spectrum disorders.

9. Boys are four times more likely than girls to develop an ASD.

10. 21% of children with an autistic spectrum disorder have been excluded from school at least once.

10 Questions Parents of ADHD Children Should Ask Their Schools

When it comes to ADHD, there are certain things that it’s important to be aware of about your child’s school.

1. What are the classes like?

“It is vital not just to meet the headteacher and to read the school policies, but to visit the school in action. Consider issues such class sizes, how the seating is arranged, and whether the children appear motivated,” Fin says. “Get a sense of the atmosphere of the school – does it feel inclusive or exclusive? Don’t consider it for the location; does the school feel right for your child? Trust your instincts!”

2. Do the teaching staff know about ADHD?

“It is vitally important that you find out in advance that the headteacher, SENCO, and teachers in the school are aware, accept and understand the learning styles of children with ADHD,” explains Fin. “This includes TAs, midday support and any other member of the school who may come into contact with the children,” adds Sheila.

3. How flexible are the teaching and learning arrangements?

“Not only do children with ADHD require flexibility in terms of teaching style and management, but many of them may have specific learning difficulties with handwriting, spelling, etc,” Fin says. “As a result, what arrangements does the school have in place to support these issues?”

4. What are the arrangements for homework?

“Studies report that children with ADHD take up to three times longer than traditional learners to complete the same piece of homework,” Fin explains. “How will the school deal with this issue?”

5. What alternative arrangements are available during unstructured time and times of change?

“Children with ADHD feel most at ease with structure and routine. As a result, it is common for most incidents to occur not during class time but during break and lunchtime periods,” says Fin. “What alternative arrangements are in place during these times that can provide greater structure? For example, are there rooms where specific supervised activities will take place at this time?”

“It’s very important to prepare children for changes – a supply teacher, or even changing a display,” says Sheila. “We know from experience that when a child’s regular teacher is not standing in front of them in the morning, this can throw them out for the day. The big one is the summer break because the children know that when they come back they will have a new classroom and a new teacher. I would ask how the school manages changes – including sudden ones.”

6. How does the school support issues of differences?

“Though it is likely that most children with ADHD will have a range of issues, there are some common traits of fidgeting, disorganization and sometimes frustration that can occur,” Fin explains. “Be upfront about this, and find out how the school would support these issues.”

7. How does the school handle bullying situations?

“Unfortunately, many children with ADHD can have problems with socialization. Because their ‘social radar’ does not always function correctly, they can annoy and irritate their peers and can, therefore, be bullied by other children,” says Fin. “Find out in advance what the school would do in these circumstances. Does a peer mentoring arrangement exist? How do they deal with bullying situations? Are there after school clubs or activities that could help develop friendship groups?”

8. Is there someone at the school who could be a mentor?

Sheila says, “It’s important to have a mentor, a regular member of staff that the child can talk to and a place they can go when they need to.”

9. What’s the best way to communicate?

“Determine who will be your regular school contact and how you will communicate with them, whether it’s by phone, text or email,” Finn recommends. “In this way, you can be quickly and regularly informed of any issues regarding your child.”

“Building up that relationship between parent and school is huge,” Shelia emphasizes. “A parent needs to feel confident that when they need to discuss their child or issues that there is someone there to deal with things and not allow issues to fester.

“However, a parent needs to be prepared to work with the school to understand the limits of what the school can provide for their child to ensure that relationship works,” she adds.

10. What is the school’s policy about ADHD medication?

“It’s important to understand the school’s attitude with regards to children with ADHD who require medication support,” says Fin. “Are they prepared to administer medication if required and/or communicate with the child’s doctor with regards to monitoring progress or issues such, side effects when necessary?”

7 Strategies To Help Defeat Children’s Fear Of Maths

What does it mean if your child has a fear of maths, and what can you do to help them get over it?

Why are some kids scared of maths?

One reason could be that maths is taught in school as a judgmental subject – very often answers are a matter of black or white, yes or no. ‘Understandably, children don’t like being told they’re wrong’, says Steve Chinn, an international consultant specializing in maths difficulties and author of The Fear of Maths: How to Overcome it (£10, Souvenir Press). ‘And having to do calculations in class – often quite quickly – if they lack confidence just increases any existing anxiety. Anxiety makes the working memory less effective – children just freeze up.’

Jo Boaler, Professor of Mathematics Education at Stanford University, US, and author of The Elephant in the Classroom: Helping Children Learn and Love Maths (£12.99, Souvenir Press), agrees: ‘Unfortunately, in most schools maths is taught as a closed subject with right and wrong answers, and children are drilled that it’s just the formal methods they have to remember. But actually, maths is an open, creative and flexible subject so as a parent you can try and give them a different experience at home.’

‘Hearing your child say ‘I can’t do maths, I’m just rubbish at it’, can be an early sign they might be going down the wrong path with the subject’, warns Jo. But the good news is that there’s a lot you can do as a parent to help them get over their fear – and even start to enjoy maths.

Strategy 1: Anyone can crack maths

‘People used to think that only some children have the ability to be good at maths. Despite the fact that theory’s been knocked down by research, many teachers still believe it – and it filters through to pupils,’ says Jo. ‘No wonder that many kids both fear maths and don’t want to engage with the subject.’

Strategy 2: Mistakes are good

When children think they’re going to fail at something, they usually don’t try. But recent research shows that the human brain actually grows most when you make a mistake in maths. Says Jo: ‘It’s ironic because children feel terrible if they get something wrong with maths. But parents need to reassure kids that it’s not only good to make mistakes, but when you struggle with maths it means your brain’s developing.’

Strategy 3: Take a guess

Estimates aren’t right or wrong, so using estimation can be very confidence building – as well as a useful life skill to have. ‘A good question to ask is, “Do you think the answer you’ve just got is bigger or smaller than the proper answer?” as it encourages children to think about the values of the numbers in their math problem,’ says Steve.

Strategy 4: Play around with numbers

In maths, the ability to play around with numbers is vital for mental arithmetic as well as real-life. It’s good to encourage children to play with numbers on paper, or with big counters in front of them. Having visual images is crucial as it reinforces the concepts in their heads. ‘There are some great simple games with dice,’ says Jo. ‘Try rolling five dice and challenging your child to make a number, 20 for example, out of the dice.’

Strategy 5: Use technology

If your child finds learning times tables almost impossible – or just really dull, a computer or smartphones can be a handy rote learning tool. Steve recommends a powerful technique called “self-voice echo”: ‘Type three facts from a times table onto the screen (for example, 5 x 8s are 40), then help your child record himself or herself reading it through in their own voice. Using headphones, they can listen to the audio over and over, while reading it aloud.’ This technique works best in short bursts of up to 10 minutes a day.

Strategy 6: Act like a maths fan (even if you’re not)

Many parents are scared of maths – particularly mums (more women than men have had bad experiences of the subject in the past). ‘Research shows that as soon as mothers comfort their daughters by saying they weren’t good at maths at school themselves, their daughter’s achievement goes down in that same term,’ says Jo. ‘So always try to greet maths homework with excitement – even if you have to use all your acting skills.’

Strategy 7: Find out more about primary maths yourself

Whether you're looking for details of what your child will learn in maths in the primary school year by year, teachers' tricks to help with new mathematical concepts or everyday games to play to make maths fun, TheSchoolRun has loads of information and practical resources to help.

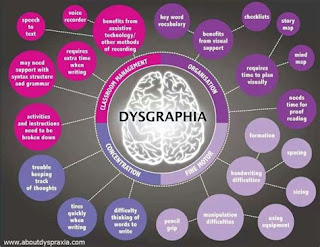

All About Dysgraphia

What is dysgraphia?

In its most general sense, dysgraphia is difficulty with handwriting that’s connected to problems with fine motor skills. It does take different forms that need to be understood in order to be treated correctly, and it’s always recommended to consult a specialist if you have any concerns.

A child with dysgraphia won’t necessarily be dyslexic or dyspraxic (though the conditions are often linked). For example, dysgraphia won’t necessarily affect oral spelling; so, a child could be an excellent oral speller, but be very poor when it comes to writing words out on paper. Because this may indicate that the condition isn’t dyslexic, it can be treated differently.

How to recognize dysgraphia

Children with dysgraphia may have excellent reading and listening skills, but they have trouble with handwritten homework. It could take a long time to do, or they may just not want to do it because of the frustrations writing causes them. Watch for these signs:

1. Difficulty holding a pen

2. Forming letters that are different sizes, with irregular spacing, and not always staying on the line

3. Illegible handwriting (something that you really can’t read at all – most children may not write neatly but it can still be read, whereas not being able to read what they’ve written at all could indicate a problem)

4. Mixing upper and lower case letters

5. Holding a pen/pencil very tightly

6. Problems with spelling

7. Lack of motivation with writing

What I can do to help my child?

National Handwriting Association committee member Catherine Elsey is a pediatric occupational therapist and recommends that parents start with basic body positioning when it comes to assessing their child’s handwriting practices before looking at letter formation.

“Look at the biomechanics first,” she says. “Find out if your child is ready ergonomically and posturally to begin writing.” Is your child comfortable where they’re sitting? Are the table and chair height right for them? Are their feet flat on the floor?

“Ask children if they get any pain or discomfort when writing, and to show you where,” says Catherine. This will tell you which part of their arm that they’re using to write. Children with dysgraphia will likely be using most of their arm to write and could have aches and pains in their shoulder, arm and/or wrist. “The most common problem I see is wrist positioning,” Catherine explains. “Most parents just look at the thumb and finger position.” Check to see if your child’s wrist is relaxed as they write and moving smoothly across the page as they do, or if it jumps along while they try to stretch their fingers to reach further along a line. “You need to go back and look at where the problem starts,” says Catherine.

When you set out paper for your child to write on, make sure it’s angled correctly, on the right or left side of the body (depending on which hand your child writes with), and not positioned flat and straight. “Right-handed writing naturally goes in an uphill movement,” explains Catherine, “and left-handed writing moves downhill. Children will end up twisting their body to compensate.”

You can work on strengthening hand and finger muscles with toys you probably already have. For instance, playing with clay and Lego will help reinforce what children need to write. “You can use any toy that requires resistance, and has a bit of push and pull,” says Catherine. Encourage your children to think about what they’re doing with their hands as they play.

If you think your child may have dysgraphia, you may find help at school. “Check what they have to help kids with handwriting difficulties,” Catherine says. They may have a handwriting group, for instance, or be able to recommend computer programmes you can try at home.”

7 Common Dyslexia Questions Answered

1. 'My child has real trouble with reading and writing. Could they be dyslexic?'

Yes, trouble with reading and writing could well be due to dyslexia; if your child's school has been teaching reading and spelling in a systematic way, in line with the National Curriculum, and your child is still struggling, then dyslexia is probably the most likely reason.

However, you should also have your child’s eyesight and hearing checked. Quite a large number of children have undetected hearing problems and this is another reason why learning to read and spell can be hard.

The only definite way to find out if your child is dyslexic is through a diagnostic assessment that a psychologist or specialist teacher can do. You do not have to wait to get such an assessment before taking action and lots of useful things can be done that is simply good practice for most struggling readers. However, if it is important to you to know for sure, or if some attempts have already been made to address the problem which hasn’t worked, then an assessment is a good idea. If the school can’t arrange this, independent organizations like Dyslexia Action can provide this service for a fee.

2. 'I think my child is dyslexic but her teacher doesn’t agree.'

The first thing to do is to get an agreement on whether there really is a problem and, if so, what needs to be done about it and to worry less about different views about what to call the problem. If there is recognition that your child has a need for support and something positive is being done, that is the main thing.

However, if you really can’t agree, or you feel the teacher thinks you are worrying unnecessarily, you can ask to meet with the school’s Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator. You can also seek an independent assessment from other independent professionals. At Dyslexia Action we find about a quarter to a third of people we assess are not dyslexic so don’t be influenced by those who think you ‘pay for a label’. It is no good at all to have the wrong label! As I’ve already mentioned, what matters most is that the right action is taken.

3. 'Homework is very difficult. What can I do to make the process easier?'

Homework can be a major challenge, but there are things that you can do to help.

Consider whether your child has a suitable place to do his/her work, which might be away from distractions for some, or listening to music for others.

What is the best time of day for your child to do homework? For some, this is mornings before school, for others straight after coming home, and for others after a snack and period of TV. Discuss with your child when the best time is, encourage a routine and try to avoid leaving homework until the last minute.

You could also talk to your child and their teachers about how messages for homework get home. It is very common for the real problem to be that children didn’t understand what they were supposed to do or didn’t make notes in a form they can read. Can instructions for homework be put on the school’s website? Can children use audio recorders to make note of instructions? Think about what systems you can use to help your child remember the right books and equipment that is needed, at the right time and in the right place.

Of course, you should not do homework for your child, but helping them organize what they need in order to do the work can make a real difference.

4.'I have a dyslexic child. What can I do to support his learning at home?'

The number one thing I would suggest you do is something completely unrelated to reading, spelling, homework or learning – make it a priority to help your child do more of something they really like and are good at!

Of course learning matters, but if you are dyslexic you will always take knocks and the most important thing to do is to withstand those knocks and get going again. If children know they can succeed and experience success and encouragement they are much more likely to believe in themselves and work through in those areas they stumble or fall.

Sometimes, of course, it is good to work on problem areas at home, but I would always encourage this to be something that is driven from the outside rather than something you impose as a parent. Be careful that you aren’t trying to help your child at a time of day that isn’t good for them or for you.

You need to be positive and encouraging and never suggest that your child has ‘something wrong with them’. This can be hard when, for example, they read a word in 5 different ways on the same page, but it will not help to get exasperated. Your main job is to be a parent, the main job of teaching falls to teachers.

5. 'I’ve read about learning aids for dyslexic children. Are they any good?'

Computer programs can play a role, but again it is better to use these as part of a plan that an expert has put together so you know what level to work at. Examples of programs to consider are Wordshark, Nessy and Dyslexia Action’s home literacy program Literacy that fits.

For older children, assistive technology is playing an increasing role. Word-processors and ‘dyslexia sensitive’ spellcheckers are invaluable, as are programs that allow ideas to be organized in a more visual way (using mind maps, for example).

6. 'Is there any help with the cost of tutors and how should I choose one?'

Not all dyslexic children need a tutor; with an understanding and supporting class teacher, and perhaps a bit of extra work that school can organize, many children with dyslexia can and do make good progress.

However, there are times when a boost can be useful and the evidence shows that taking action early is generally most effective in the long-term. If you do use a tutor, it is really important that you get someone who understands about dyslexia and can offer a range of types of support, ideally, go through an organisation like Dyslexia Action where all tutors are trained to Postgraduate level, have regular updates to their training and are subject to quality assurance routines.

The costs of specialist support over a long-term do add up, but support may be available through local bursary funds, for example. Remember, however, that a short period of the right kind of highly targeted specialist support can make more difference than many hours of more general learning support.

7. 'Are dyslexic children allowed to use the computer more?'

Typing isn’t necessarily easier than handwriting, but there are enormous advantages to using a word processor both for checking spelling and getting a neatly legible printout.

I support the idea that handwriting matters and all should be taught it. In fact, many people with dyslexia learn to spell better using what is called the ‘kinaesthetic’ method which involves developing a kind of movement memory for the way words are produced. However, some people with dyslexia have extra difficulties with motor control and for them, it is important to investigate what works best for them individually.

In general, schools are using keyboards much earlier than they used to and there is no evidence that this is making handwriting worse.

Dyspraxia: Parents' Questions Answered

Dyspraxia, or Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD), causes problems with language, perception and thought – most specifically issues with coordination. Around one in seven children has this learning difficulty and if your child is affected it can be hard to know how to help for the best. Here we answer some of the most common questions parents ask.

1. How can I get a dyspraxia diagnosis for my child?

Getting early intervention and the right support for dyspraxia is important to help your child learn coping strategies and achieve their potential – both at school and in everyday living. ‘First talk to your child’s teacher and see if they have any concerns, then ask if the school has a referral pathway for dyspraxia or DCD,’ says Dr Amanda Kirby, the UK’s leading authority on dyspraxia, author of Dyspraxia: Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (£12.99, Souvenir Press) and herself a mum of a dyspraxic child. ‘If there isn’t a referral pathway in place, you’ll need to see your GP and discuss a referral to a pediatrician.’

After a referral comes to the assessment process. You’ll answer questions about your child including when they first sat up or crawled, plus they’ll be tested on gross motor skills (like running, walking and balance) and fine motor skills (like writing and doing up buttons).

What help is my dyspraxic child entitled to in school?

Dyspraxia affects your child’s ability to learn so they may need extra help at school. ‘While there’s no specific help outlined, under the Equality Act 2010 every school in the UK has a legal requirement to support children with a disability,’ says Amanda. Depending on your child’s specific needs, their school can do things like providing extra supervision, give longer to learn tasks, and provide equipment to help (the umbrella organization Movement Matters offers guidance on options open to primary schools).

2. How can I help with my child’s handwriting?

Writing can often be a problem with children with dyspraxia. ‘There are different parts of writing and not all of those are motor related’, says Amanda. ‘Some children have handwriting difficulties because they don’t know how to make the letter shapes rather than having poor control.’ What can help is practicing drawing the letter shapes correctly with your child? ‘Make it more fun by drawing them in the sand, or in foam in the bath’, she suggests. ‘Also experiment with pencil grips as some children find that certain grips give more stability and make writing more comfortable.’

Posture when writing is important, too. It’s best is to sit up straight with feet flat on the floor or resting on a stool or box. Some experts also recommend a writing slope, a portable slope that can help them write at the best angle. Long-term, learning to touch-type is a useful skill to learn, particularly if your child finds it hard to write quickly or for long periods.

Any practical tips to help my dyspraxic child at home?

Lack of coordination can make even the simplest everyday tasks tricky for dyspraxics. The website Box of Ideas, part of the Discovery Centre at which Amanda is a medical director, contains tips and tricks for helping with independent living skills including:

A- Eating

1. A suction pad or damp flannel under their plate so it doesn’t slip.

2. A deep bowl or a plate with a rim will minimize spillages.

3. A cup with two handles (easier to grip than a single-handled cup) and one that’s weighted or slightly heavier (less likely to knock over).

B- Dressing

1. Encourage your child to get dressed sitting down as it makes them more stable.

2. Show your child how to lay out tomorrow’s clothes in the order they’ll put them on. For example, pants first, then socks, then T-shirt, etc. Try to turn this into a nightly routine.

3. Avoid fastenings, as they make it harder for your child to dress themselves. Velcro and poppers are easier than laces on shoes.

4. Choose trousers with a pleat at the front and tops with a logo or pattern so it’s easier to tell which way round they go.

C- Routine

Following a daily routine can help children with dyspraxia, and a good way to present this is as a visual timetable. Being able to refer back to it themselves when they need to is a way to boost their self-confidence. For example, break down a task like brushing teeth into different steps, taking a photo or drawing a picture for each step. Stick the pictures onto pieces of card and laminate both sides, and then attach to a notice board with Velcro fastenings. The idea is that when your child completes each task, they can put them in a ‘done’ folder so they see what they’ve achieved – and what still needs to be done that day.

Does My Child Have Dyscalculia?

What are the signs to look out for a child might have dyscalculia or 'number blindness', and what can be done to help?

What is dyscalculia?

If you haven’t heard of dyscalculia, you may have heard of the term ‘number blindness’. Other people liken it to ‘dyslexia with numbers’. In a nutshell, the Department for Education says dyscalculics struggle to understand simple number concepts, ‘lack an intuitive grasp of numbers, and have problems learning number facts and procedures.’

What are the dyscalculia signs to look out for?

Children with dyscalculia find it hard to learn maths techniques that are taught at school, like adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing. ‘In general, they often have problems with understanding and remembering the basic concepts of arithmetic such as the basic number facts or recognising “how many”’, says Steve Chinn, a maths expert with many years' experience teaching children with learning difficulties and author of Dealing with Dyscalculia and The Fear of Maths: How to Overcome it (£10, Souvenir Press). ‘Often they remain heavily reliant on counting in ones, rather than recognizing and using quantities greater than one.’

If you notice these specific issues in your child by the time they reach the Reception class at primary school, you may have cause for concern:

1. Poor one-to-one correspondence. When we count out coins on a table, most of us move each coin distinctly with a finger as we separate it from the pile. An early sign of dyscalculia is if your child doesn’t touch or move the coins while trying to count them out. ‘Children in Reception class at primary school are expected to be able to reliably count out 10 objects’, says Steve.

Failure to recognize small quantities. Early number sense means understanding early number names and attaching a label to small quantities. For example, if you ask your child to look at four random objects laid on a table then say how many there are. ‘By Reception, we’d expect children to be able to identify four objects by sight,’ Steve says.

2. Difficulty recognizing that different quantities are bigger and smaller when represented as objects or digits. This ability is about an early understanding of addition, subtraction, and estimation.

What can I do to help my dyscalculic child at home?

‘You can’t cure dyscalculia – whatever the underlying difficulties, they’ll probably remain – but you can make a difference to it,’ says Steve. There are lots of counting activities you can do around early numbers with your child if they’re struggling. ‘Encourage them to play around with numbers to improve their number sense, and see the numbers within numbers,’ he continues. ‘For example, recognizing that four is one more than three, and is one less than five, and is two lots of two.’ Use things that they can touch, feel and see, as children with dyscalculia often find it easier to learn using concrete materials. Here are some more ideas:

3. Estimation. Put two sets of items on a table, for example, eight items next to three items, then four items next to three items. Ask ‘Which is the bigger number? Which pile has less?’ Teaching your child to appraise quantity and estimate is a valuable skill.

Working with counters. Put four counters in a square shape then ask your child what they see. Cover up two counters, so they see it’s two lots of two. Next cover up three so they learn it’s three and one.

4. Practice forwards and backward. Children with dyscalculia can have problems counting back and forth, particularly when it comes to twos and threes.

5. Break down prices. Shopping is a great chance to play around with numbers. If you see something that costs 69p, point out its 50p and 10p and 9 pennies. Or it’s 50p and 20p, and you’d get a penny back.

How should I approach my child's school if I’m concerned about dyscalculia?

‘Official dyscalculia screening starts from seven’, says Steve. ‘That’s not to say that you might not have cause for concern any younger, but it’s very hard to diagnose before that age because of other normal developmental issues.’ Start off by asking a teacher if they’ve noticed your child have problems with numbers. Find out their ideas, and if they have any programmes for children making low progress in maths. They might not have much knowledge of dyscalculia or how best to teach a dyscalculic pupil, so it’s good to be able to suggest resources that can help, if necessary